Dursun Yıldız

Director

Hydropolitcs Academy-Türkiye

After the worst drought in 40 years, water insecurity poses a deadly risk to children in the Horn of Africa (Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia).(Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Horn of Africa Countries.

Climate change is leading to increasingly unpredictable variations in temperature and rainfall patterns in the Horn of Africa, a trend that is only expected to intensify. While some areas may receive higher rainfall, much of the region will suffer from decreased rains. The average temperature increases are also projected to rise higher and faster than the global mean(1).

Decreased rainfall will cause lower levels of surface water and limit the replenishment of groundwater aquifers – two important sources of water for communities. These decreased water levels, in conjunction with poor sanitation and hygiene, give rise to deadly waterborne diseases such as cholera and acute watery diarrhoea. Increased temperatures cause more water to evaporate from land and water surfaces, leading to lower soil moisture and greater water losses from reservoirs. This impacts agricultural production and the availability of water for household use. Intense heat can also damage water infrastructure and increase the risk of water-borne pathogens that thrive in warmer temperatures. Too much water, in the form of extreme rainfall events, also threatens water supply, as floods damage infrastructure, pollute wells and dislodge pipelines. Low-lying wastewater treatment facilities are particularly at risk. In much of the Horn of Africa region, water scarcity has resulted in demand for water resources that exceeds the available supply. In short, there is not enough water to meet the growing needs of children and families, as well as agriculture, energy, industrial, and ecosystem needs

Growing Drought Crisis

After facing the worst drought in more than 40 years between 2021 and 2023, the Horn is now once again facing a growing drought crisis after failed rains in 2024 and 2025. This is leading to food and water shortages, as well as the potential loss of livestock and future harvests.

Kenya is facing a significant drought crisis, primarily due to the failure of seasonal rains since late 2024. The country’s National Drought Management Authority has confirmed that 20 out of 23 counties in the arid and semi-arid lands are experiencing worsening drought conditions. (3).

In Somalia, poor rainfall, flooding and persistent conflict are driving 3.4 million people into high levels of acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 3 or above) across much of the country. Between July and September 2025, around 624,000 people experienced emergency levels of acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 4), while more than 2.8 million people experienced crisis levels (IPC Phase 3). (3).

The Somali Region in eastern Ethiopia has also experienced multiple consecutive poor rainfall seasons since 2021. In 2025, the start of the main pastoral rains (the “gu/genna” cycle) failed in large parts of the region. This has resulted in low pasture and water availability, deteriorating livestock conditions.(3).

Recurring droughts

Drought has been a recurring issue in the Horn of Africa, with drought fuelling the 2011 famine in Somalia, in which over 260,000 people died. Since 2011, Somalia has had only one proper year of rainfall (in 2013) with all other years falling far short of the norm for one or both of the two rainy seasons per year.(3).

The 2021-23 drought was the worst in 60 years in Kenya and Somalia, following five failed rainy seasons. Some 23.5 million people were impacted, 13.2 million livestock died, and seven million children were acutely malnourished.

But since 2011 humanitarian assistance has increased significantly, and resilience and Early Warning Early Action approaches have also contributed to saving lives. This has meant that the impact of the droughts has lessened, and a declaration of famine has been averted, although in 2023 almost 400,000 people experienced famine conditions in Somalia.(3).

Water Crises in the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa faces one of the world’s most severe and persistent water crises. This crisis is shaped by the interplay of climate variability, hydrological stress, weak governance, and regional conflict dynamics.

The Horn of Africa’s water crisis is a multifaceted crisis exacerbated by the confluence of climate, population pressures, governance weaknesses, and transboundary tensions. A sustainable recovery for the region is possible through basin-scale planning, data-driven management, and climate-resilient policies.

A Way Forward

The region needs to consider water not merely as a “resource,” but as a strategic lever for regional development and peace. Regional development projects must be developed in line with this approach.

The following steps should be taken to help the region overcome the water crisis:

Climate-resilient water infrastructure

Groundwater mapping & monitoring

Basin-scale cooperation

Water-energy-food nexus planning

Early-warning systems

Transboundary Hydropolitics in the Horn of Africa

The physical, socioeconomic, and political challenges in the Horn of Africa with regard to water resources are acute. Three-quarters of the people in the region live within river basins and over aquifers that are shared by two or more countries.

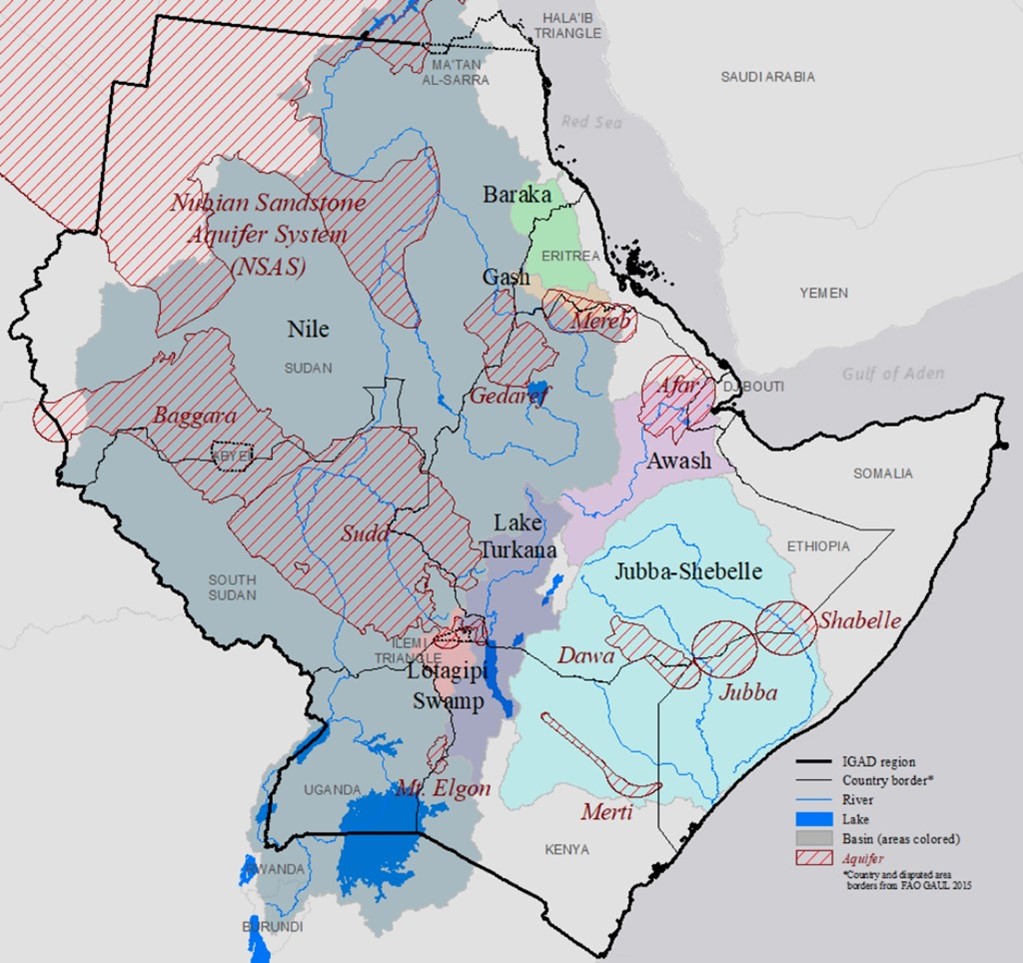

Figure 2. Map of the shared basins and aquifers in the project area / UNEP-DHI

Cross-border river basins and aquifers are entirely contained within the IGAD region (8 countries), as well as the Nile basin and the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer System, which extend beyond the region(4). (Fig.2)

The Horn of Africa—mainly Ethiopia, Somalia, Eritrea, Djibouti, and indirectly Kenya and Sudan—is shaped by a complex set of transboundary hydropolitical dynamics. River basins in this region face both high climate vulnerability and a weak institutional framework, making water a geopolitical force.

The main transboundary rivers of the Horn of Africa are:

Juba–Shabelle Basin (Ethiopia–Somalia)

Awash Basin (Ethiopia → Djibouti, with partial impacts on Eritrea)

Omo–Turkana Basin (Ethiopia–Kenya)

Baro–Akobo–Sobat (Ethiopia → South Sudan → Nile)

These basins make water critical for both state power and livelihood security.

Transboundary hydropolitics in the Horn of Africa is a high-risk water-geopolitical arena shaped by asymmetrical power balances, institutional voids, climate uncertainty, and critical interdependence. Unless countries in the region develop cooperation mechanisms, water crises will continue to deepen in terms of both humanitarian and regional security.

References

- UNICEF Regional Call To Action Horn Of Africa Drought Crisis: Climate Change is Here Now July 2022

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/aaba1b#:~:text=5%20%C2%B0C%20GWLs%20is,faster%20 than%20the%20global%20mean

- UNICEF Horn of Africa Drought Situation Overview, April 27, 2022

- Concern Worldwide (2025) Concern is supporting communities impacted by Horn of Africa drought https://www.concern.net/press-releases/concern-supporting-communities-impacted-horn-africa-drought

- Cross-border basin delineation: UNEP-DHI and UNEP, TWAP (2016), cross-border aquifer delineation: IGRAC, TWAP (2016).